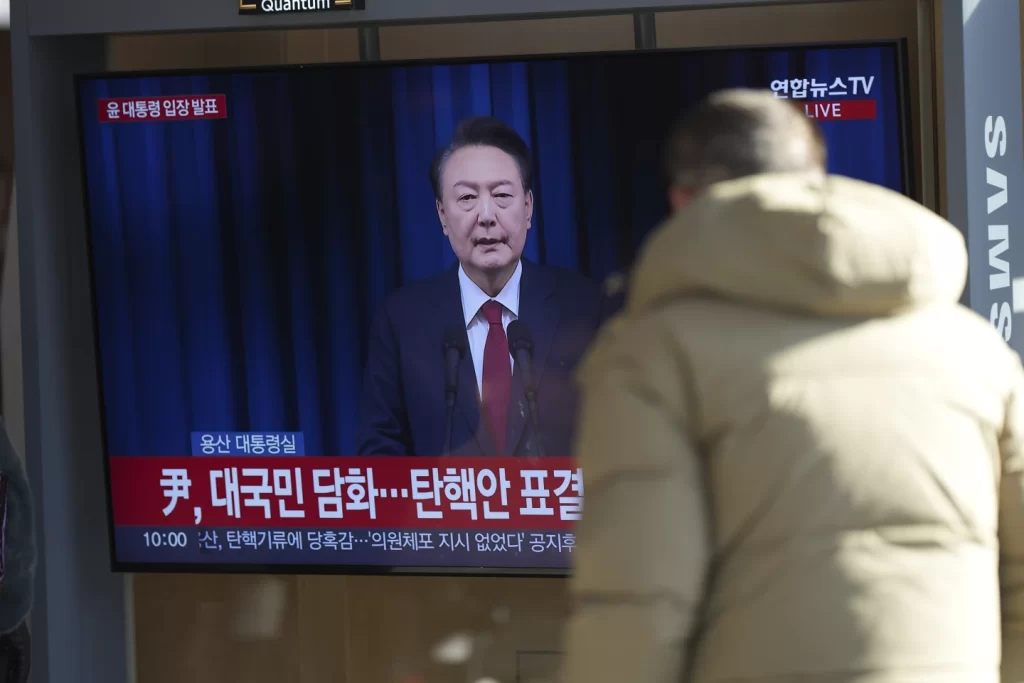

South Korean President Yoon Suk Yeol issued a public apology on Saturday for his attempt to impose martial law earlier this week, which was widely criticized and sparked national protests. Yoon acknowledged the public anxiety caused by his actions in a brief televised address, stating he would take full legal and political responsibility. He also pledged not to pursue martial law again and left the resolution of the political crisis, including decisions about his presidency, to his conservative People Power Party (PPP).

The National Assembly is scheduled to vote later on Saturday on whether to impeach Yoon. This follows escalating protests nationwide and increasing political pressure for his removal. The impeachment motion, filed by opposition lawmakers, needs a two-thirds majority—200 of the 300 National Assembly members—to pass. Opposition parties hold 192 seats combined, requiring support from at least eight members of Yoon’s own party.

The controversy began when Yoon abruptly declared martial law on Wednesday, labeling the opposition-controlled parliament a “den of criminals.” The declaration prompted immediate backlash, including a unanimous 190-0 vote by the National Assembly to annul the measure just hours later. The vote occurred under extraordinary circumstances, with heavily armed troops encircling the parliament in an apparent attempt to disrupt proceedings and detain opposition leaders.

Yoon’s actions have been described by critics as a “self-coup,” with opposition lawmakers drafting the impeachment motion on rebellion charges.

The crisis deepened as allegations emerged that Yoon had ordered South Korea’s defense counterintelligence unit to arrest and detain key politicians during the brief imposition of martial law. Among those reportedly targeted were opposition leader Lee Jae-myung, National Assembly Speaker Woo Won Shik, and even PPP leader Han Dong-hun, who has called for the suspension of Yoon’s presidential powers.

Han, who lacks voting rights in parliament, revealed that he had received intelligence about Yoon’s plans to detain politicians based on accusations of “anti-state activities.” The National Intelligence Service’s first deputy director, Hong Jang-won, confirmed in a closed-door briefing that Yoon had requested assistance in detaining lawmakers.

The Defense Ministry has taken action against officials involved in enforcing martial law. Yeo In-hyung, commander of the defense counterintelligence unit, has been suspended, along with Lee Jin-woo, head of the capital defense command, and Kwak Jong-geun, commander of the special warfare command. Former Defense Minister Kim Yong Hyun, accused of recommending martial law, is now under a travel ban and faces rebellion charges.

Vice Defense Minister Kim Seon Ho, who assumed the acting minister role after Yoon accepted Kim Yong Hyun’s resignation, testified that Kim Yong Hyun had ordered the deployment of troops to the National Assembly following Yoon’s martial law declaration.

The political turmoil has paralyzed South Korea’s government and raised alarm among international allies, including Japan and the United States. The impeachment vote could lead to Yoon’s suspension and the appointment of an interim leader. However, it remains unclear if the motion will secure the necessary bipartisan support.

As South Korea grapples with one of its most significant political crises in recent history, the outcome of Saturday’s vote could determine the future of Yoon’s presidency and the stability of the country’s democratic institutions.