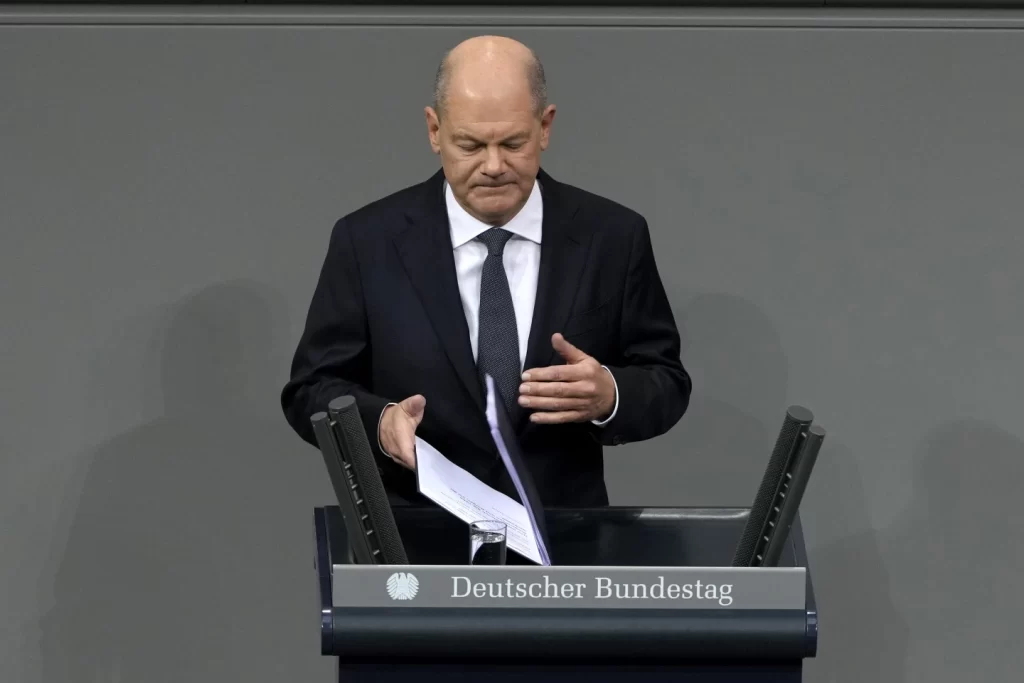

Chancellor Olaf Scholz failed to secure a confidence vote in the German Bundestag on Monday, setting the stage for an early election in February and plunging Germany, Europe’s largest economy, into political uncertainty.

Scholz received support from only 207 lawmakers in the 733-seat lower house, with 394 voting against him and 116 abstaining. Falling well short of the required majority of 367, Scholz’s defeat marks a significant turning point for the country as it grapples with economic stagnation and political gridlock.

The vote comes after the collapse of Scholz’s three-party coalition on November 6, when he dismissed his finance minister over disputes regarding how to address Germany’s economic struggles. With the government now operating as a minority, leaders of major political parties have agreed to hold elections on February 23, seven months earlier than originally planned.

Under Germany’s post-World War II constitution, parliament cannot dissolve itself, so the decision now rests with President Frank-Walter Steinmeier. Steinmeier has 21 days to formally dissolve the Bundestag, a step expected to take place after Christmas. Once dissolved, elections must be held within 60 days.

While formalities are pending, campaigning has already begun, as highlighted by the tense exchanges in Monday’s parliamentary session.

In his address to lawmakers, Scholz, leader of the center-left Social Democrats (SPD), framed the upcoming election as a choice about Germany’s future direction.

“This election will determine whether we, as a strong country, dare to invest in our future. Do we have confidence in ourselves and our potential, or do we risk our prosperity by delaying necessary reforms?” Scholz said. His campaign proposals include modernizing Germany’s strict debt rules, raising the national minimum wage, and reducing value-added tax on food.

Friedrich Merz, leader of the center-right Union bloc and Scholz’s primary challenger, criticized the chancellor’s handling of the economy, calling it one of the country’s worst postwar crises.

“You’re leaving Germany adrift during an economic downturn,” Merz argued. “Running up debt at the expense of future generations is no solution. You didn’t even mention the competitiveness of Germany’s economy in your speech.”

On foreign policy, Scholz reaffirmed Germany’s role as Europe’s largest supplier of military aid to Ukraine but ruled out sending long-range Taurus cruise missiles or German troops. “We will do nothing to jeopardize our own security,” he stated.

Merz, who supports the possibility of sending the missiles, pushed back but noted that Germany’s political leaders share the “absolute will” to see the war in Ukraine brought to an end as soon as possible.

Recent polls show Scholz’s Social Democrats trailing far behind Merz’s opposition Union bloc, which currently leads the race. Vice Chancellor Robert Habeck of the Greens has also entered the contest, though his party remains in third place.

Meanwhile, the far-right Alternative for Germany (AfD), led by Alice Weidel, is polling strongly but remains politically isolated, as other parties refuse to collaborate with it.

Germany’s proportional electoral system makes coalition governments the norm, and no party is expected to secure a parliamentary majority on its own. The election will likely be followed by weeks of negotiations to form a stable coalition government.

Confidence votes are unusual in Germany, a nation that places great value on political stability. This is only the sixth such vote since World War II. The most recent occurred in 2005, when then-Chancellor Gerhard Schröder triggered an early election, which resulted in a narrow victory for Angela Merkel.

Germany now faces an uncertain political future, with economic challenges and foreign policy priorities set to dominate the upcoming election.