MEXICO CITY — Mexico is facing mounting scrutiny ahead of its first-ever judicial elections on June 1, as candidates with criminal records, past cartel ties, and histories of judicial misconduct appear on the ballot for federal judgeships — a development critics warn could severely undermine the rule of law.

Among the most controversial figures is Leopoldo Chavez, who served nearly six years in a U.S. prison after being convicted in 2015 of smuggling over four kilograms of methamphetamines. Despite his record, Chavez is now running for federal judge in Durango, part of the cartel-dominated Golden Triangle region.

“I’ve never sold myself as the perfect candidate,” Chavez said in a Facebook video, defending his right to run. He has declined interview requests from Reuters.

In Jalisco, former judge Francisco Hernandez is campaigning for a criminal magistrate post, despite having been removed from office following a federal investigation into allegations of sexual abuse and corruption. He insists the charges were “slander and defamation,” telling Reuters: “Let the people judge me.”

Fernando Escamilla, a candidate in Nuevo Leon, hopes to become a federal criminal judge. He previously provided legal counsel to attorneys for members of the notorious Los Zetas cartel. He defended his past, emphasizing his expertise in extradition law: “Does being an advisor on international law damage your reputation? I don’t think so.”

The presence of such candidates has ignited criticism from legal experts, civil rights organizations, and judicial associations. Defensorxs, a Mexican human rights group, has flagged at least 20 candidates with troubling backgrounds, including prior criminal convictions, corruption allegations, and links to organized crime. The group says many slipped through a rushed and flawed vetting process.

At the center of the controversy is Silvia Delgado, a former defense attorney for Joaquin “El Chapo” Guzman, the infamous Sinaloa Cartel leader. Delgado, now running for a criminal court judgeship in Chihuahua, represented El Chapo during his extradition proceedings and visited him regularly in prison.

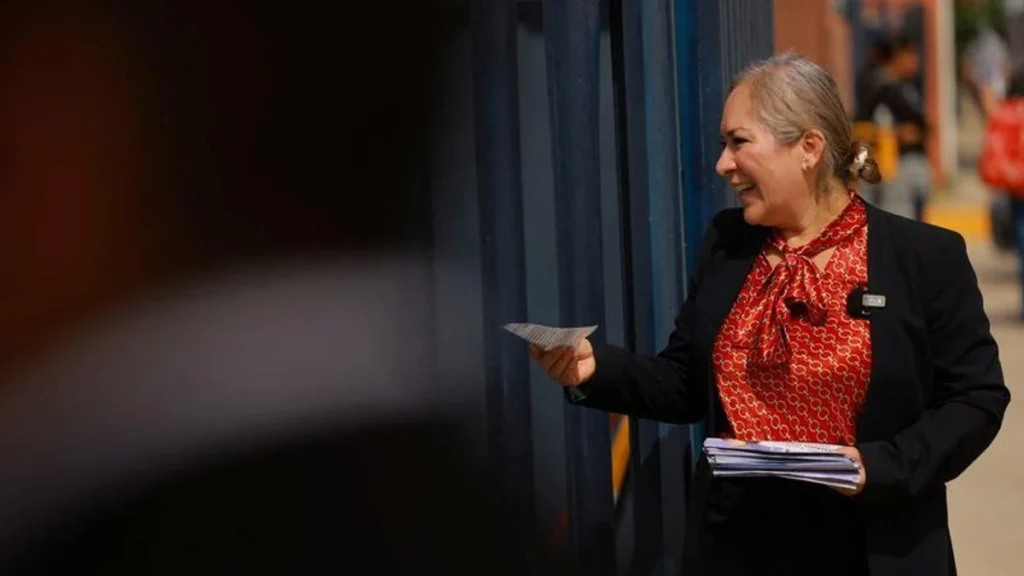

“I’m not corrupt,” Delgado told Reuters during a campaign stop in Ciudad Juarez. “They can’t burn you for having represented someone.” A single mother who put herself through law school, Delgado said she took the high-profile case as a career opportunity and would do so again.

But Miguel Meza, president of Defensorxs, said Delgado’s candidacy raises serious concerns about vetting standards. “We’re not attacking candidates — we’re informing the public of the risks they represent,” Meza said, noting his organization continues to identify more problematic contenders.

The election is part of a sweeping judicial reform passed in September 2024 and championed by leftist former president Andres Manuel Lopez Obrador, with strong support from his successor, President Claudia Sheinbaum. The reform aims to eliminate corruption by letting voters choose judges, but critics argue it opens the door for cartel influence and political manipulation.

Under the new law, more than 5,000 candidates are competing for 840 federal positions, including all Supreme Court justices. The reform reduces the number of Supreme Court judges from 11 to 9, cuts term lengths to 12 years, lowers the legal experience requirement from 10 to 5 years, removes the minimum age of 35, and introduces a five-member disciplinary tribunal to oversee 50,000 judicial workers.

JUFED, Mexico’s judges’ association, has called the reform a threat to judicial independence. “What’s happening with the election is dangerous,” said JUFED director Juana Fuentes. “There is a serious risk that criminal interests could infiltrate the judiciary.”

Most sitting Supreme Court justices have chosen not to participate in the elections and plan to resign instead.

Candidates are banned from linking themselves to political parties, participating in party events, or accepting donations. However, critics argue that these restrictions are insufficient to prevent deeper systemic risks.

Senate leader Gerardo Fernandez Norona, a prominent member of the ruling Morena party, dismissed concerns as a media campaign driven by “racist, classist” bias. “It’s not important. It’s not relevant,” he said, adding that ineligible winners can be removed post-election.

The National Electoral Institute (INE) acknowledged flaws in the process and confirmed that ballots cannot be altered before the election. Claudia Zavala, an INE advisor, criticized the fragmented vetting process led by a committee of congressional, executive, and judicial appointees.

Any post-election review of a candidate’s eligibility must conclude by June 15, before results are certified. If a winner is disqualified, the position will go to the runner-up.

Despite the mounting backlash, neither Sheinbaum’s office nor the federal judiciary has commented publicly. With less than three weeks until the vote, concerns remain over whether the process will truly enhance transparency or simply deepen Mexico’s legal and political crises.