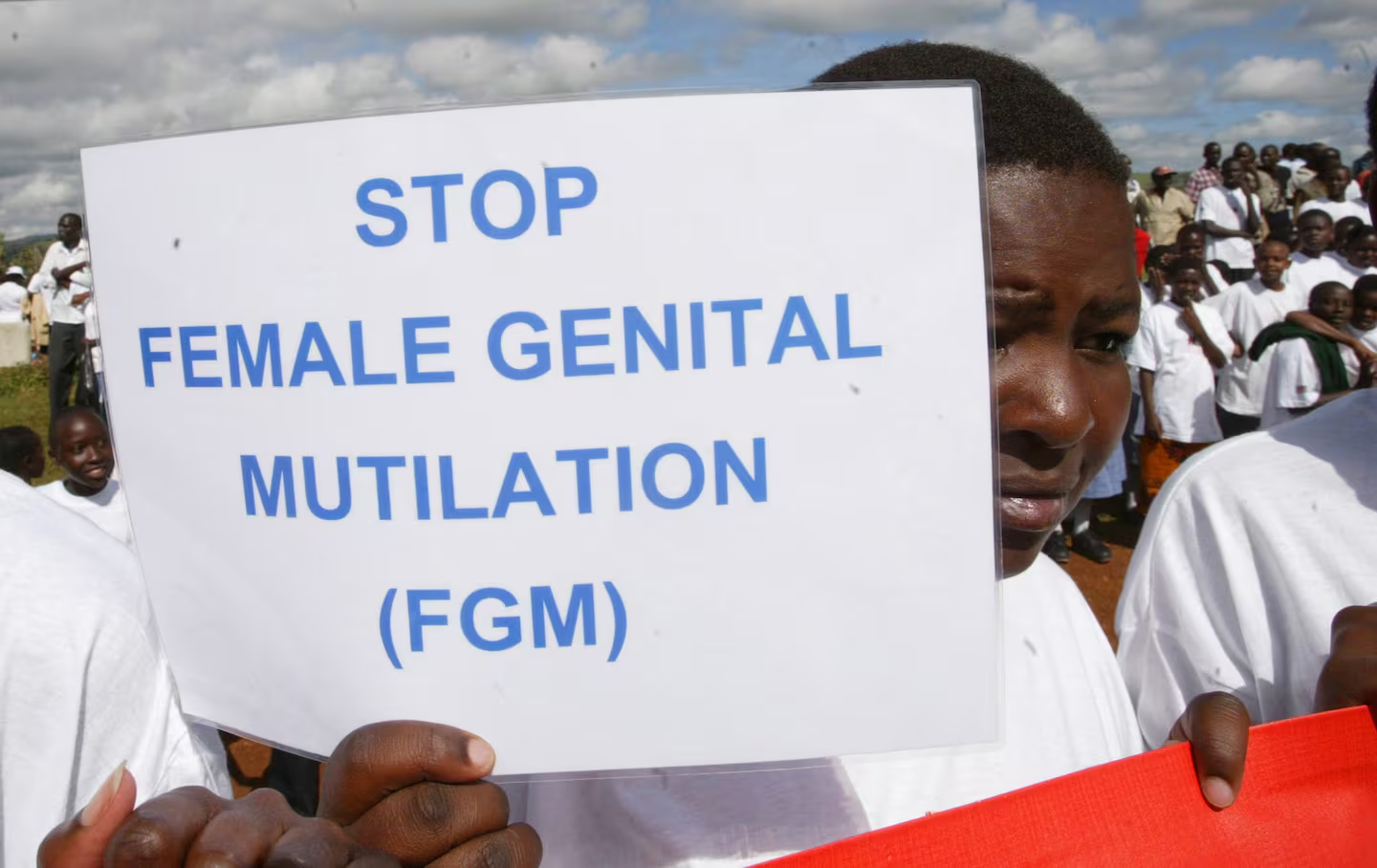

Gambia’s recent parliamentary decision to uphold its ban on female genital cutting (FGM) has been hailed as a victory by rights groups, but the real battle continues in the country’s rural areas. The debate over reversing the ban, which would have been a global first, brought the issue into public discourse for the first time in the West African nation of less than 3 million people.

Women like Metta, a mother of six from rural Gambia, traveled to the capital Banjul to protest against reversing the ban. Despite the legislative victory, activists face significant challenges in changing deeply rooted cultural practices. The United Nations estimates that about 75% of women in Gambia have undergone FGM, a procedure the World Health Organization classifies as a form of torture.

Local activists are treading carefully, aware that their efforts could be jeopardized by too much attention. Women in rural areas are often reluctant to speak out against the practice, fearing backlash from their communities. Some activists have received hate messages for their stance against FGM.

The debate has revealed deep cultural divides. Supporters of FGM argue that it’s rooted in Gambian culture and Islamic teachings, while opponents see it as a violation of women’s rights. Habibou Tamba, a 37-year-old activist, received messages accusing him of serving Western interests after participating in anti-FGM protests.

Awareness meetings in rural areas reveal mixed reactions. While some women are shocked by the health complications associated with FGM, others defend it as a cultural and religious practice. The story of Rabietou, a 42-year-old mother of six, illustrates the generational impact of FGM and the potential for change. Cut as a child and married at 15, she now advocates against the practice for her youngest daughter.

Metta’s personal journey from undergoing FGM at age 8 to protecting her own daughters from the practice demonstrates the slow but significant shift in attitudes among some rural women. However, the prevalence of FGM and the sensitivity surrounding the topic indicate that the fight against this practice is far from over in Gambia.

AP